A New Median Voter Theorem

1. The Traditional Median Voter Theorem (MVT)

What is it?

The basic story of the median voter theorem goes like this: all voters sit on an ideological spectrum, as do politicians. In each election, voters vote for the candidate whose ideology is perceived to be the most similar to their own. Thus, the candidate with the ideology that’s closer to a majority of voters — that is, the candidate whose ideology is closer to the median voter ideologically — wins the election.

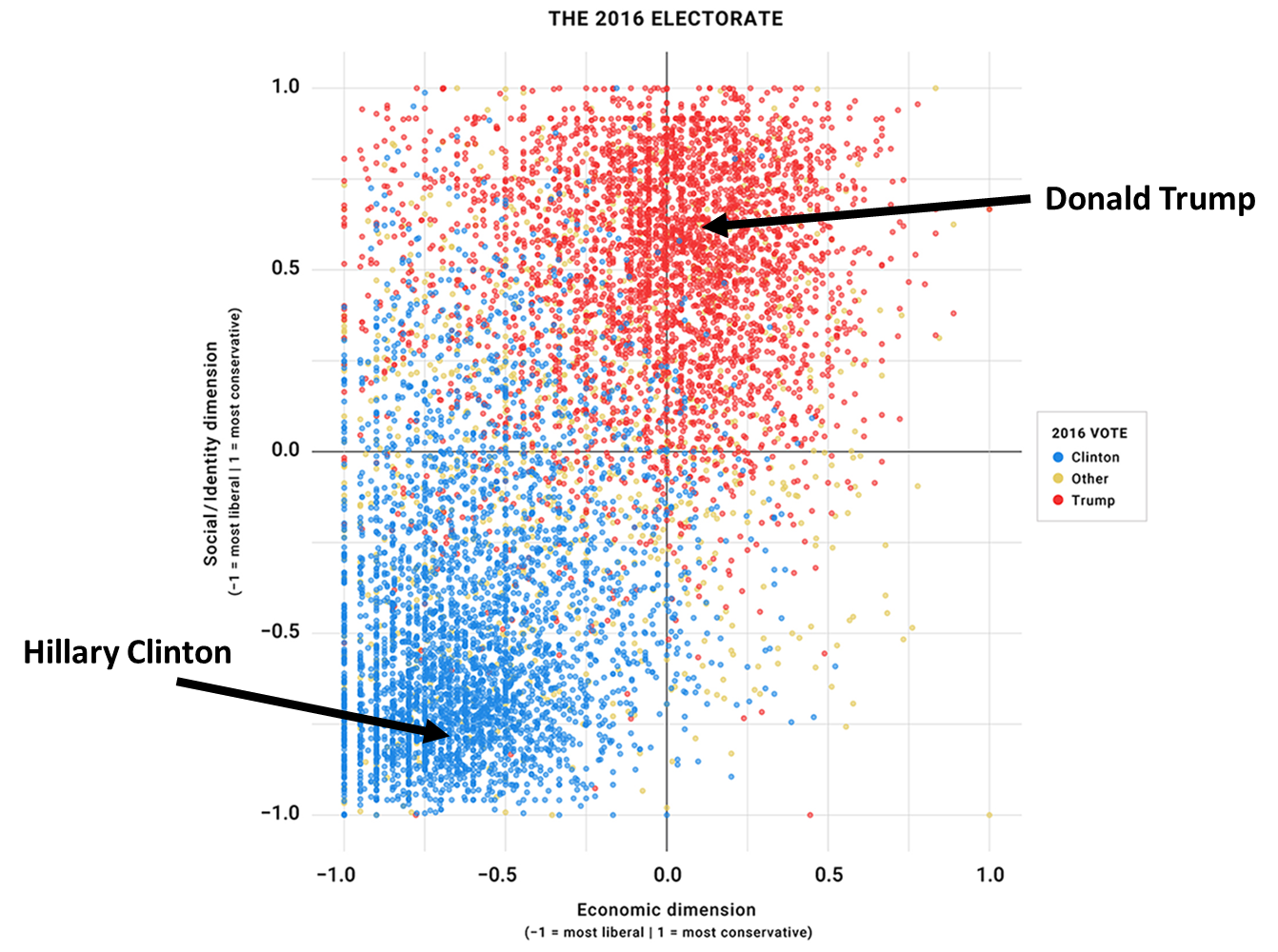

You could also easily expand this to multiple ideological dimensions (though in that case there is no one “median” voter). This might be a more accurate description of, say, the social vs. economic ideological axes in politics. Despite the many problems with the below chart, it is true that this distinction is an important one in American politics

You could imagine this chart modelling the 2016 election from a MVT perspective:

If you consider that you can have a dimension for each political issue, and that voters can weigh each dimension a different amount (based on how important that issue is to them), this becomes a very general tool for modelling elections.

How accurate is it?

A model is only as good as its relation to reality.

If you’re a college-educated liberal without much exposure to David Shor’s ideas, you might be surprised to see the 2016 election as evidence of the median voter theorem. Doesn’t Trump’s insane rhetoric and constant violation of democratic norms make him a more extreme candidate than Hillary was? Well, voters didn’t see it that way. There are a lot of polls showing Trump was perceived as closer to the median voter’s ideology than Hillary was

It is worth digging into why this is. The standard answer among liberals is that Republicans’ constant use of the terms “radical left” and “far-left” cause voters to view the Democratic party as further left than it actually is, and that Democrats should be calling Republicans “far right” if they wanted it to be symmetric. There are certainly several metrics showing that Democrats are in fact closer to the center: issue polls predominantly support the Democratic positions by decent margins, Republicans are less concerned these days with the previously bipartisan enthusiasm for democracy and experience, and massive bipartisan spending deals — where most of the bipartisan action in Congress ends up — are basically only opposed by a portion of the Republican party.

But there is probably more at play. Rhetorically, Trump said a lot of contradicting things, particularly on economic issues, that likely convinced voters he was more moderate. The thing that Trump was publicly super radical on — authoritarianism — simply isn’t very important to swing voters. His being radical on social issues did hurt him among college-educated people, they just don’t count as much in the Electoral College and Senate.

When he came into office, Trump enacted a lot of legislation that you might not traditionally associate with Republicans. The budgets and omnibus bills passed under Trump saw public spending in line with Obama-era increases, and the CARES act took this to all new heights under the pandemic. It is in some ways unsurprising that voters would view Trump as moderate on economic issues.

Setting aside how voters saw this, I don’t want to overstate the extent of this moderation on economic issues. Most of this legislation was by necessity bipartisan, and there’s reason to believe a Republican party with filibuster-less majorities would enact far more radical policy. Trump’s budget proposals in 2019, 2020 and 2021 were standard Republican cuts to Social Security and Medicare (oddly not 2018, though it still drastically cut other social programs), and by the end of his term Trump was even threatening to veto the bipartisan omnibus bills. Executive branch appointments, which Republicans did have unilateral control over under Trump, were either further right than Bush (see climate, illegal immigration) or just a bunch of Bush nominees (a lot of economic stuff). The justices that Trump got confirmed were further right than Bush, too.

All this said, presidential elections can’t provide solid evidence one way or the other for the median voter theorem, given how few of them there are. The plentiful lower level election data, however, does provide evidence that moderate candidates outperform their extreme counterparts. A 2002 studied found a correlation between overperformance and voting against your own party. A 2015 study found a correlation between a moderate candidate winning a primary (“moderate” measured by how ideological the interest groups that donated to the candidate were, ie how consistently their candidates stuck to the party-line vote) and their party overperforming on election day. The same was found to be true in 2019 on the governor and state legislature level.

A follow-up to the 2015 study found that this effect was caused by extreme candidates galvanizing the opposite party’s base to show up, which is less consistent though not entirely inconsistent with the median voter theorem. Persuasion definitely plays a big role too though, something seen by private campaign research as well as (declining but still substantial) ticket-splitting in elections.

2. The Directional Median Voter Theorem

Disclaimer: I assume I am not the first one to discuss these ideas. Still, I have not come across much discussion of this online, and I think it’s an important topic.

A common sense check

Is the traditional model really the way voters see issues? If you asked a voter for their ideal corporate tax rate or minimum wage, would they really give you a solid answer? And is the candidate they vote for really the one whose number is most similar to their own?

There is some evidence that voters think like this. A 15$ minimum wage is less popular than a 10$ minimum wage, according to polls. More qualitatively, different gun control measures poll differently, which suggests that voters have some level of gun control they support, instead of “nobody can buy guns” or “there should be no restrictions at all”.

That being said, I think in many cases it’s pretty absurd. Specifically, most voter issue positions are which direction they would like to move status quo policy rather than the ideal policy they would implement. It is simply a lot easier to think about what action needs to be taken (“we need to raise taxes on the rich”) than to envision what ideal policy would look like (“the top tax bracket should be x%). The same thing is true for political parties: they are seen as ideological directions to shift the status quo rather than specific ideological policies. Democrats are seen as the party of more gun control, not as the party of “universal background checks, assault weapon bans, and national gun registry but also allowing most citizens to own handguns”.

There’s also some hard evidence that voters think this way. Swing voters usually have a mix of liberal and conservative positions rather than moderate ones (see below). Additionally, voters trust Republicans more on a lot of issues where specific policy questions consistently favor Democrats (see minimum wage, gun control, and illegal immigration). The traditional response to this is that polls are all written by liberals, infusing bias into the questions themselves, though I don’t find this entirely satisfactory: a lot of these question wordings (definitely not all!) seem perfectly accurate and unbiased. I think it’s likely that, at least to some extent, voters have a vague sense that policy should be pushed into a certain direction (and vote accordingly), even if they don’t specifically know what should be enacted.

The new model

Embedded in election rhetoric is the fact that voters largely see politics as a set of “issues” which you must then take action to remedy. This implies a different version of the MVT than is traditionally described, which I will call directional MVT. This version goes as follows: the importance (real or imagined) of different problems in the status quo affects which policies voters think should be adopted. They then vote for the political party that promises to push policy in that direction. When a party takes power, it takes actions which (at least in perception) alleviate some of those problems and create different new ones. This then causes voters to perceive different issues as having higher importance, which shifts which parties voters are willing to support.

This version keeps the idea that voters weigh different ideological dimensions based on how important they are to voters, which in this version simply determines how important it is to the voter that his/her ideological direction corresponds to the candidate’s.

In the directional median voter theorem, the median voter still controls elections, but does so based on which policies they are willing to tolerate from the incumbent party (through their perception of these policies’ impact), rather than which set of policies they aspire to. One could imagine that this set of tolerable policies is a voter’s ideal policy, in which case this version becomes a lot more similar to traditional MVT, but this is unnecessary and I think pretty unrealistic.

A hypothetical diagram for the 2016 election can be seen here. Under directional MVT, the main factor explaining Trump’s victory is him shifting the median voters’ importance from economic issues to social issues, rather than being moderate on economic issues.

Evidence

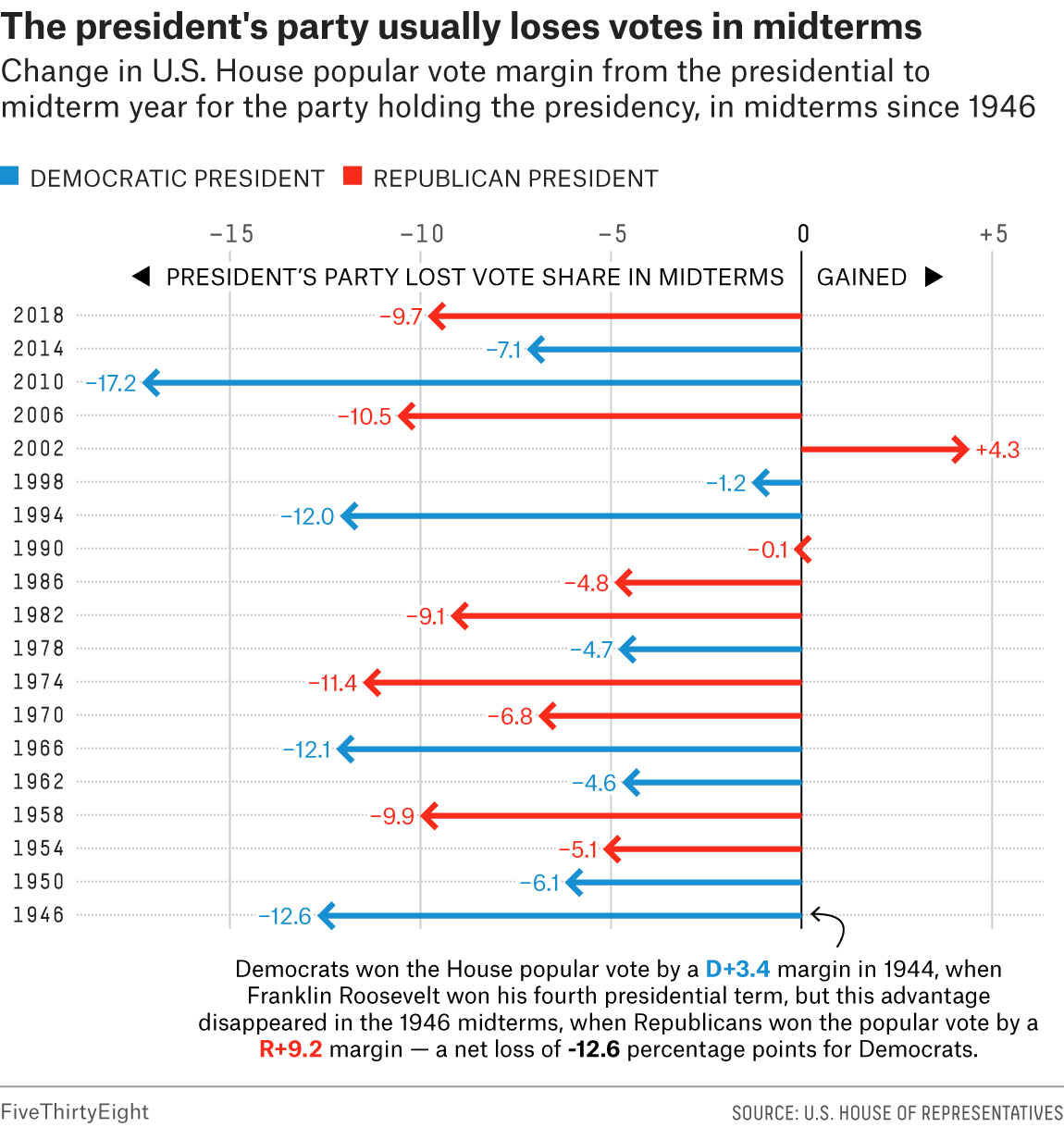

The traditional median voter theorem does an ok job of explaining why certain candidates outperform others, especially downballot. The best evidence for this new MVT is the central tenant of the theory: backlash, one of the most consistent trends in democratic politics. Almost every time a political party wins a presidential election in the US, the opposing party does well in the following midterm. This trend can’t really be explained by the traditional MVT; the opposing party cannot be consistently moderating that much after each election. And a significant portion of this backlash is not persuasion, not turnout —public opinion on issues really does change!

Backlash is also seen when Republicans governors in deep-red states or Democratic governors in deep-blue states who enact very aggressive policy are so unpopular that the opposing party manages to win the governorship (see here, here, here, and here).

Finally — and this sort of goes with how I first presented the issue — most of the time after a president has served two terms in office, the party with the presidency changes. Yes, parties try to moderate to take power, but this can’t be the only factor in such a consistent trend, and I highly doubt it’s the main one.

3. What can we learn from Directional MVT?

Despite the differences between this new MVT and the traditional theory, the prescription for center-left parties across the globe trying to stave off far-right populism is largely the same: moderate on cultural issues, focus on economic issues. The two theories disagree on why exactly this should work: directional MVT says it is because swing voters will vote more based on their preferred direction for shifting economic policy rather than social policy, while traditional MVT says it is a mix of this reason and the fact that swing voters will be ideologically closer to the center-left.

These theories both also argue that an equilibrium will occur even in biased electoral systems. The US (if it survives straight-up election stealing) is about to enter a phase of consistent, large bias against Democrats in the Senate (call it R+8; Democrats have to win by ~8% three elections in a row to win the Senate). The old red-state Democrats are mostly gone, and the few remaining will likely be gone soon due to higher polarization. Under traditional MVT, you would expect the parties to reorient around appealing to not the median voter, but the 46th percentile conservative voter; that is, Republicans will try to change their policy platform to consistently get to 46% of the vote, Democrats to 54%. Under directional MVT, this is mostly still true: if Republicans take actions that more than 54% of voters disapprove of, you’d expect Democrats to take power. Symmetrically, if Democrats take actions that more than 46% of voters disapprove of, you’d expect Republicans to take power.

So how should directional MVT cause us to think any differently? I would argue that, due to its greater common sense and increased explanation on why voters hold the views they do (rather than just how the system will react to these views), directional MVT is a more of a humble theory. When traditional MVT fails, you are basically forced to do one of two things. You can throw your hands up, declare that voters are irrational and that there’s no theory that will explain it. Or you can rationalize what happened, arguing that the ideological spectrums aren’t what we think they are and that MVT is still true if you knew how voters truly see policy.

When directional MVT fails, as I think it has in many cases, there is still a lot of room to understand politics. Two ideas I could come up with that come from directional MVT’s failures:

Lacking in information about policy a politician has actually enacted (information that is really hard to aggregate!), voters will assume that a politicians’ policy matches their rhetoric. There’s basically no federal policy to enact on “defunding the policy”, but since Republicans so actively oppose it, voters assume they are doing something to prevent it. After all, government policy is a mess of interaction between federal and local govts; it’s not reasonable to expect voters to understand how it all works.

Voters use the economy as a direct indicator of the president’s policy success because how else are you supposed to tell whether complex policy has been good for the country? Causality is really hard, even if you’re a social scientist!

Final Thoughts

I don’t claim that this directional MVT is strictly better than traditional MVT. Real politics is some mix of directional MVT, traditional MVT, and many other explainable and unexplainable factors. I am just genuinely surprised people don’t discuss this theoretical model much. It provides a strong counter to the attempts to justify everything in terms of traditional MVT, a tendency that comes from it being the only theoretical model people know about. Political analysts’ theoretical horizons need some broadening.